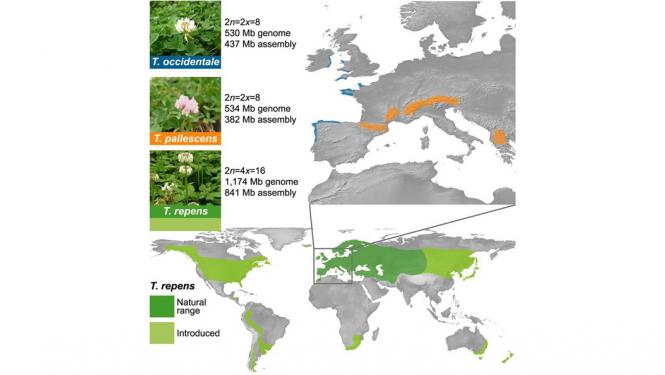

White Clover (Trifolium repens L.) is the most important and widely used pasture legume in the world today. It can be found growing from the Arctic Circle to all parts of the temperate regions of the world (see Figure 1). Agronomically, white clover ranges from a perennial plant in temperate areas to a winter annual in sub-tropical or limited summer rainfall regions.

White clover is a true breeding species that arose from the mating of two clover species sometime during the last European glaciation; probably 15,000 to 28,000 years ago (see Figure 1). One of the species, Trifolium pallescens, is found naturally in high alpine areas. The other species, Trifolium occidentale, natural habitat is coastal within 100 meters of the shore. These two species now operate genetically within white clover making it a functioning allopolyploid.

White clover was introduced into the USA with the European colonists. In fact, the indigenous peoples referred to it as “white man’s foot-grass” because it seemed to appear simultaneously with the early settlers. These spots can be found today as naturalized ecotypes (see Figure 2). Naturalized ecotypes have recently become important parents for developing new intermediate type cultivars.

Botanical Characteristics

The main distinguishing characteristic of white clover, and one that helps separate it visibly from the other clover species, is its almost round seedhead or flowering structure composed of many individual flowers (see Figure 1). These flowers are white in color, but can have a pinkish hue. It is this white flower color that is responsible for the name of the species.

White clover produces a high number of seedheads, generally in the late spring and summer, making it a prolific seed producer and natural “re-seeder” under even grazed conditions. This re-seeding ability is one characteristic that allows the species to persist as a naturalized population for long periods of time even in a grazed, pasture environment.

White clover’s spreading habit of growth is achieved via an extensive system of creeping stems called stolons (see Figure 2). These stolons are smooth, solid, vary in number and size, and are capable of rooting at each stolon node. This rooting ability is one method the species achieves its perennially when the main plant established at seeding dies. It is also the mechanism that allows the plant to spread and compete with grasses in a grazed, mixed species pasture environment. Higher stolon numbers is another excellent mechanism tied to the persistence of the plant; higher numbers lead to better probability of survival during stress times.

Leaves and their petioles are mostly smooth and arise from the stolon nodes. Leaves are compound usually containing 3 heart-shaped leaflets (trifoliate). Each leaflet possesses a white V-shaped water mark as a very distinguishing feature. It is a polymorphic plant (defined as occurring in various forms, leaf sizes, and spreading ability).

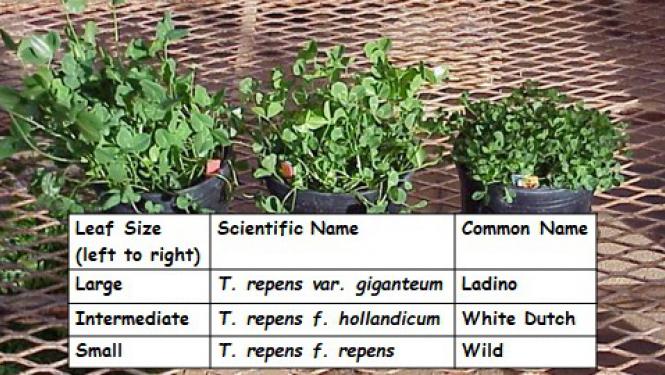

Botanically, there are three distinct, true breeding polymorphic forms of white clover based mainly on leaf size (see Figure 3):

- the large leaved, ladino type (T. repens var. giganteum Lagr-Foss). Simply called ladino.

- the medium/intermediate leaved, common type (T. repens f. hollandicum Erith ex Jav. & Soo); also called intermediate or Dutch white.

- the small leaved, wild type (T. repens L. f. repens L.); also called wild or weedy type.

Ladinos are distinguished from the other two forms by being almost exclusively acyanogenic (e.g. produces none or a very low number of plants which are capable of producing cyanogenic acid). Although found in intermediate and wild type plants, this acid is not toxic to livestock. On average, plants from ladino populations are taller and higher yielding than wild or intermediate types. Stolon and seedhead numbers are higher in the intermediate forms which usually lead to better spreading and better persistence in pastures via more stolon live over and better reseeding ability due to higher seedhead numbers.

Uses

The commercial seed market targets white clover cultivars for pasture, hay, haylage, cover crop, wildlife plots, and erosion control in the southeastern USA. It is normally planted in mixtures with grasses.

Varieties

Historically, ladino cultivars have dominated the market due mainly to their upright growth and high yield. But ladinos can have poor persistence; demonstrating only short term perennially. This problem led to development of more adapted, persistent, and grazing tolerant ladino types. However, it was recent development and release of very persistent intermediate type varieties derived from naturalized ecotypes that became most important for insuring long term pasture persistence (see Figure 2).

It is also possible to hybridize intermediate and ladino types to produce stable hybrid populations that have higher stolon density than ladinos, but larger leaves than the intermediates. Due to their leaf size and ability to produce cyanogenic acid, these hybrids are classified as intermediates.

Dutch White is definitely the prototypical intermediate, and defines the medium leaf "type" in the USA. It is what in some circles would be called 'Common' in many species, but got the name Dutch White because early agronomists felt most of the seed brought by the settlers came from Holland (even look at part of its current scientific name for intermediates, hollandicum). It is true breeding as a botanical population (as a population average) for leaf size, stolon density, and cyanogenic acid traits. Its yield is definitely variable and usually low compared to modern intermediates or intermediate x ladino hybrids (like Renovation). Actually, the first named intermediate, southeastern USA variety was 'Louisiana S-1' that was probably selected directly from a "Dutch White" population.

There is some overlap between Dutch White and wild type. The best way to see the wild type is to look for white clover growing in very closely mowed lawn and turf situations (even in golf greens under 1/4" mowing) and compare its leaf sizes and stolon number and thickness with true intermediates and ladinos.

University performance trials and some seed dealers now categorize their white clover varieties as ladino or intermediate types. Check out their webpages for more information; for example http://www2.ca.uky.edu/agcomm/pubs/PR/PR770/PR770.pdf.

Establishment and Management

It is recommended that producers refer to the book Southern Forages by D.M. Ball, C.S. Hoveland, and G.D. Lacefield for all planting and management advice with any forage crop including white clover. However, here are a few issues to keep in mind for white clover:

- Broadcast or drill seed at 2-3 lbs per acre with, or into, perennial grasses such as tall fescue or orchardgrass either in fall (October-November) or late winter to early spring (February-April).

- When inter-planting into existing grass pastures, grass competition is a major problem so limit nitrogen fertilizer use, and use grazing or mowing to reduce grass shading on the clover seedlings.

- Moderate to high P & K fertility levels are best and pH should be above 6.0.

- Herbicides like Grazon to control problem broadleaf weeds in grass pastures will kill white clover. Work with your extension agent to select the best weed control program that insures white clover survival.

Conclusions

A concluding story told by Dr. Carl Hoveland, UGA Forage Agronomist. He had met two farmers whose pastures were separated by a perimeter fence. One farmer had plenty of white clover while the other did not. The farmer with the poor stand said he planted white clover once, but after a couple of dry years, lost stand and did not replant. The farmer who had a great stand said after the establishment year he broadcast an additional pound of white clover seed each year over his pasture during the late fall-winter whether he needed to or not. A good practical lesson for everyone to attain and keep good clover stands!